This week:

China is making a dent on foreign tech imports, helped both by increased R&D spending and “poor man’s innovation.”

Weekly Links: German robotics, Hong Kong’s tech investments, and an industrial strategy for Britain.

How much foreign tech has China replaced?

Nearly a decade ago, China set the goal of becoming a “manufacturing superpower” by 2025, and an “innovation superpower” by 2050.

Implicit in those ambitions is the desire to be at the global forefront of science and technology, and by extension increasing other countries’ reliance on it while reducing its own dependence on foreign tech and know-how.

How is it doing in pursuit of those goals?

Catch up and supersede

On manufacturing, China’s strength in key industrial sectors is hard to dispute. But it’s not resting on its laurels. Though China already dominates strategically important industries, Beijing sees plenty of work ahead for cementing and extending that lead.

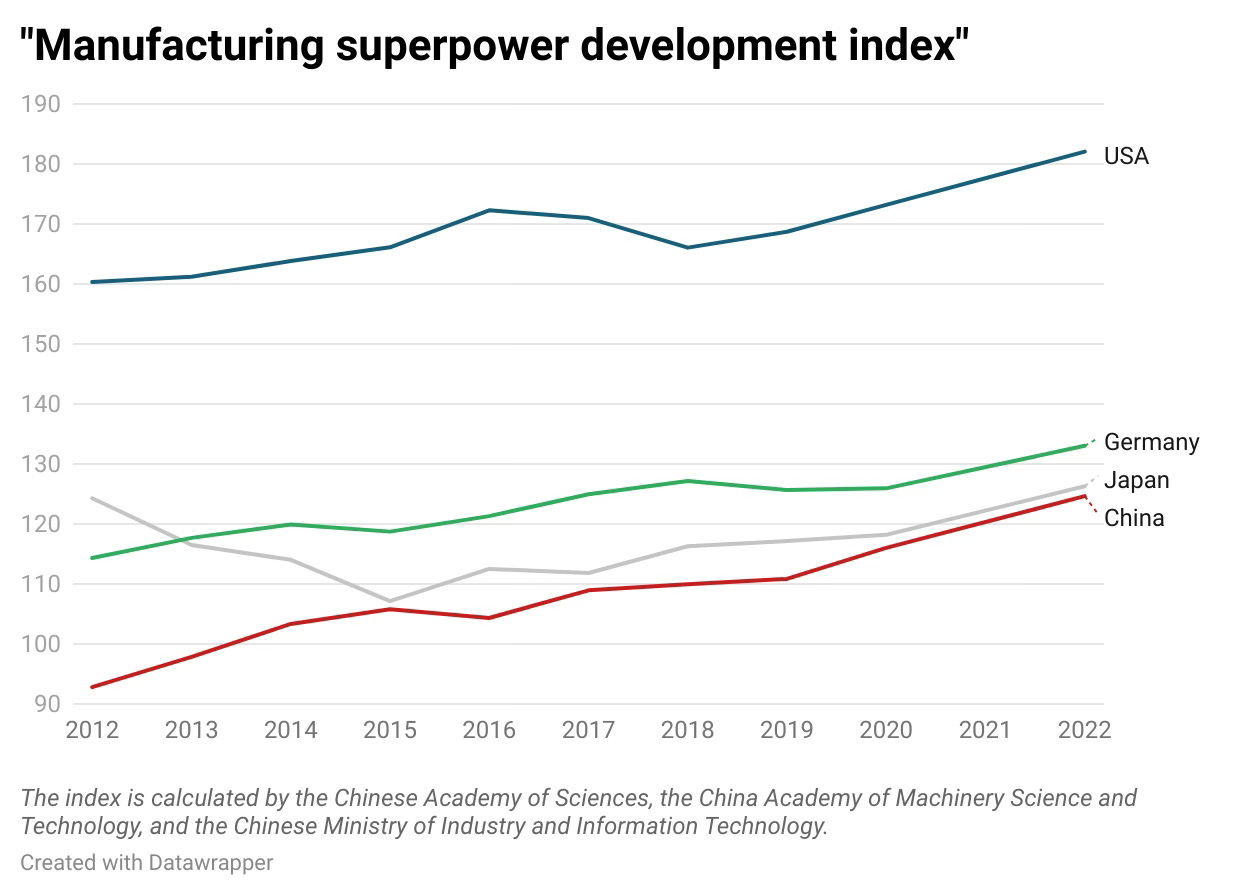

Consider the “manufacturing superpower development index,” a useful indicator of how China views its manufacturing prowess relative to other leading countries.

Developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the index shows China in fourth place globally as of 2022, catching up to Germany and Japan but still lagging considerably behind the US.

The index’s various components and their respective weightings are also indicative of Beijing’s view on what it takes to be a manufacturing superpower.

Notably, one of the most important factors is basic industries’ value added as a share of the global total.1 That reflects the Chinese government’s enduring prioritization of industrial foundations, and its recognition that even the most cutting-edge technology is often dependent on basic upstream inputs.

Returns on investments in innovation

Innovation can be trickier to quantify.

Output of patents and scientific papers are widely used to measure how innovative a country is. But they don’t fully reflect the quality of innovation, or how that innovation is applied. Nor do they reflect the types of innovation not captured by patents or journal articles.

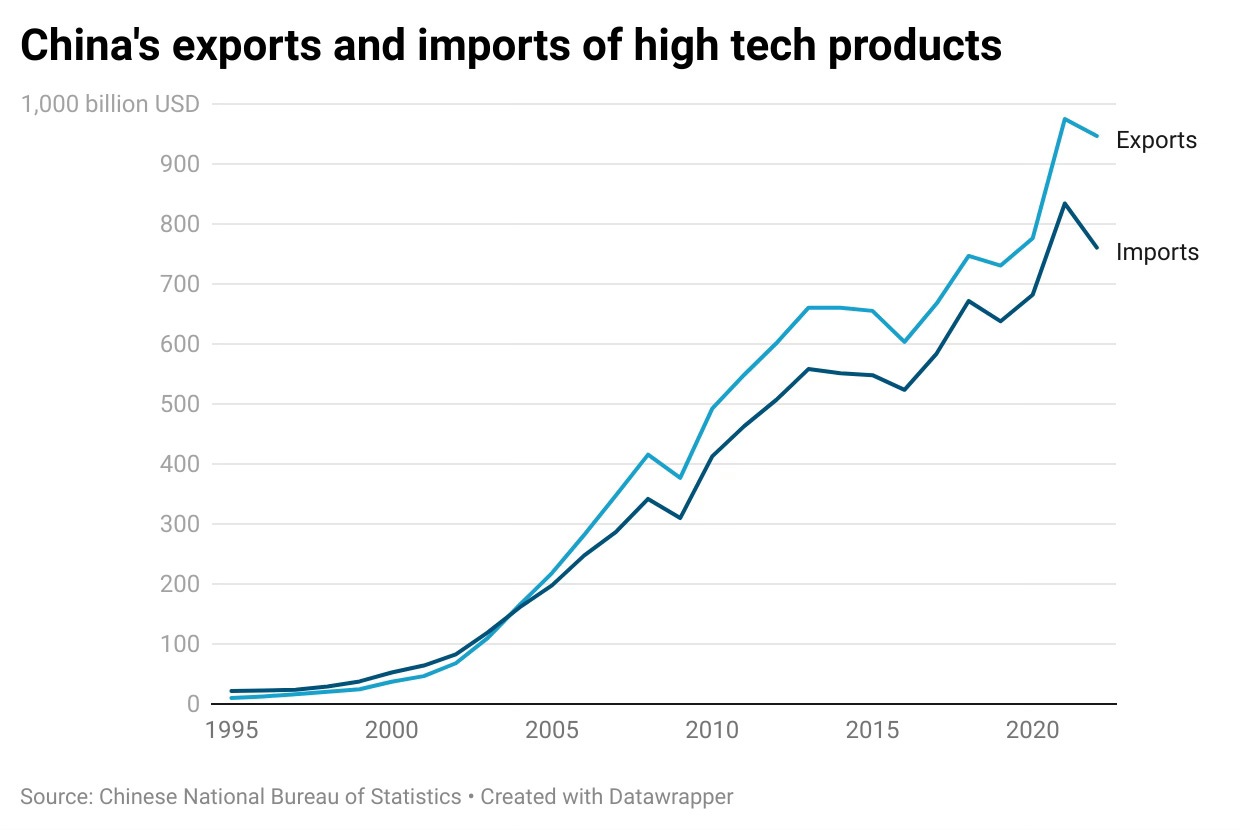

While no single indicator is perfect, another measure we might turn to is China’s imports and exports of high-tech products.

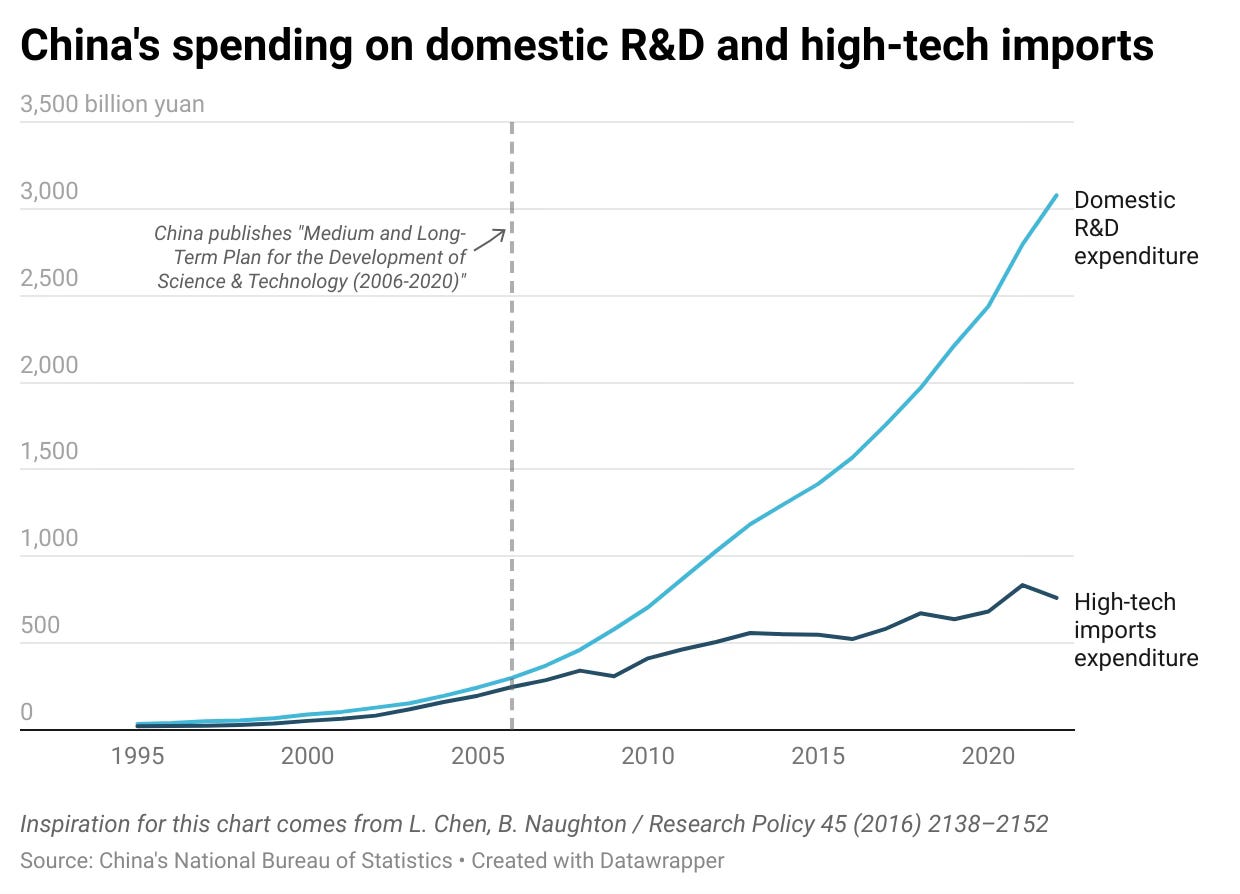

Until 2002, China spent more on high-tech imports than it made on high-tech exports. That changed in 2003 — just as China made what has been described as “a dramatic return to ‘techno-industrial policy’” involving direct state interventions in specific industries.

It was also right around this time that Beijing began promoting “indigenous innovation” as central to a 15-year science and technology plan it launched in 2006. Domestic R&D spending rose dramatically.

For much of the next two decades, high-tech imports and exports mostly grew in tandem. Then came a sharp drop in high-tech imports in 2022, aligning with Beijing’s intensified push to replace foreign tech with domestic alternatives.

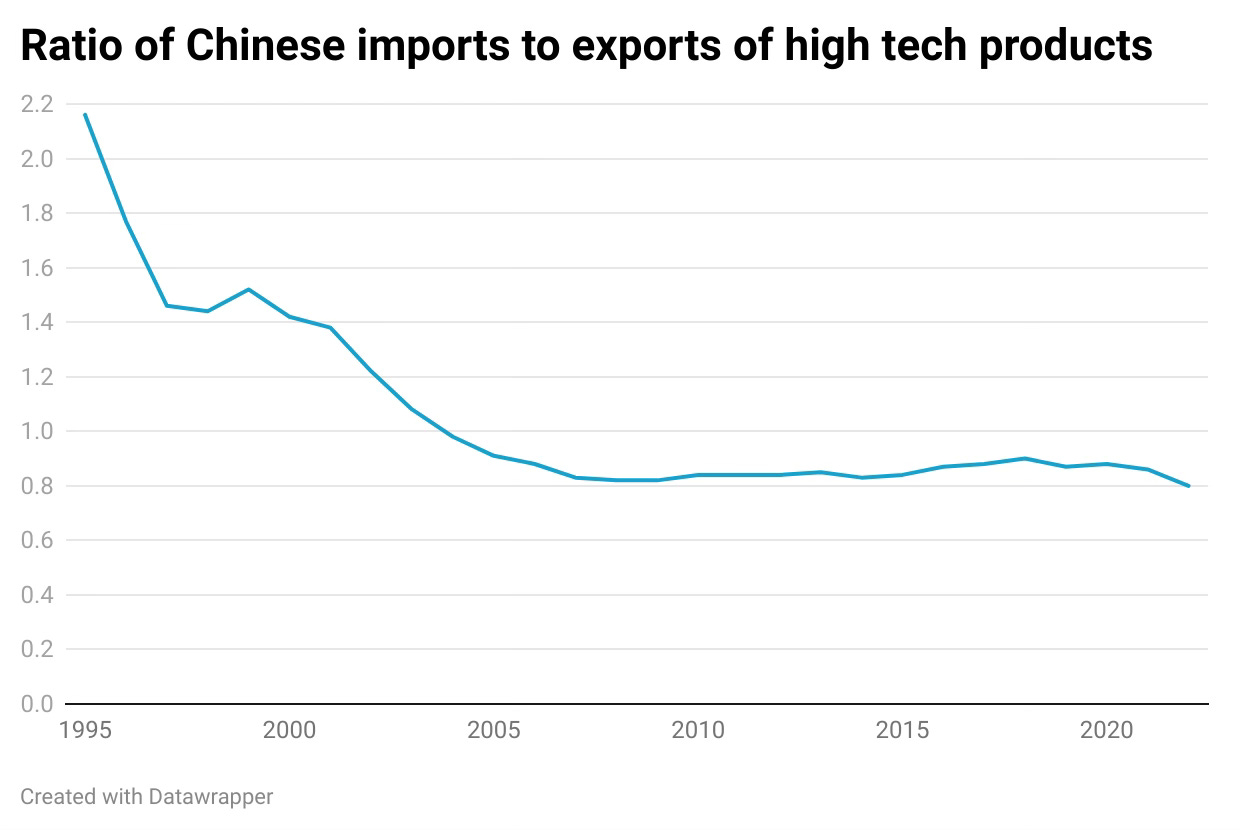

Another way of looking at it is to take the ratio of Chinese high-tech imports to exports.

That ratio saw significant declines through the early 2000s, then stayed remarkably stable throughout the aughts and 2010s — perhaps reflecting the long lead time for investments in basic R&D to manifest as applications outside the lab.

There were small declines in the ratio of Chinese high-tech imports to exports in 2016 (a year after Beijing launched its Made in China 2025 strategy) and 2019 (a year after Washington slapped major tariffs on Chinese goods). The dip in 2022 was the largest in 15 years, just as de-risking emerged as a global zeitgeist.

“Poor man’s innovation”

As China’s campaign for technological self-sufficiency kicks into high gear, we will likely see its foreign tech imports continue falling in the years ahead.

But the country will also want to keep sourcing high tech products from abroad — not least so it can absorb foreign know-how, innovate on making those products more cheaply and at greater scale, adapt them for different uses cases, and re-assemble existing technologies into new ones.

Some Chinese industry players have called this type of work “poor man’s innovation” because of its low cost. It has also been highly effective. China will probably be keeping it in its toolkit for some time yet.

Weekly Links

🖇️ Germany’s robotics industry feels the heat from Chinese competitors. VDMA, which represents German machinery and equipment manufacturers, says they face “fierce” competition as Chinese robotics firms push into Europe. It doesn’t help that Germany sold off its homegrown Kuka robotics firm to China in 2016. Those robots are now making Chinese satellites, as we pointed out recently. (Reuters)

🖇️ Hong Kong’s role in China’s tech strategy. The government-owned Hong Kong Investment Corp. recently made its first public investment in Chinese industrial AI startup SmartMore. The move marks a shift in the city government’s strategy “as part of a comprehensive effort to transform the city into a tech hub as geopolitical pressure builds,” report Cissy Zhou and Peggy Ye.

Elswhere, analyst Sunny Cheung notes that Hong Kong — with its free capital flows, and relatively easy access to both foreign and domestic data — is positioning itself as a key node in China’s tech strategy, including by facilitating the evasion of US export controls. (Nikkei Asia, The Diplomat)

🖇️ British manufacturers want an industrial strategy for the UK, according to a survey of over 300 companies conducted by industry body Make UK. The group’s senior economist said the next government must capitalize on cooling prices and possible rate cuts to “[deliver a modern, long term industrial strategy which goes beyond the 2030s and has cross government support.” (Reuters)

Other components of the manufacturing superpower index include manufacturing value added; number of leading global manufacturing brands, manufacturing workers’ productivity, and global invention patent authorizations per unit of manufacturing value added.