The industrial basics of critical tech

Why it’s important to control “the thing to make the thing to make the thing to make the thing”

Welcome to a/symmetric, published by Force Distance Times. Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric.

This week:

Back to basics: Washington’s new export control regime reflects a new recognition that upstream inputs and midstream processes—and not merely the end product—is key to national security. That’s the good news. More soberingly, China has a two decade head start on investing in basic industrial inputs.

Weekly Links Round-Up: China’s nitrocellulose challenge. The Pentagon needs to buy more ammo. Plus: is that an American or Chinese drone?

The industrial basics of critical tech

A broad point of consensus among Washington and its allies is that China’s industrial policies and mercantilist growth strategy have massively distorted the global playing field—with serious ramifications for the economic and national security of Western nations.

Efforts to nudge China away from its non-market practices and towards abiding by WTO commitments are seen to have largely failed.

Plan A, centered on persuasion and engagement, was a flop. Urgently needed now is a Plan B. What should that look like?

That was the focus of discussion this week at a congressional hearing on key economic strategies for leveling the US-China playing field, hosted by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

In particular, we want to highlight testimony from Kevin Wolf, a partner at Akin Gump and former top Commerce Department official.

He outlined the US government’s new, incipient approach to technology development and regulations as they relate to national security, and how that manifests in a new export control regime.

“The thing to make the thing to make the thing to make the thing”

Washington fundamentally revamped its approach to export controls with two packages of measures unveiled in October 2022 and October 2023, targeting AI, advanced chips and chipmaking equipment, and supercomputers.

Compared to “traditional” measures targeting things like nuclear weapons and conventional military items, the new approach is “in direct response to two things,” says Wolf:

(i) China’s overt policy of using the civil items at issue to modernize its military to give its weapons and advantage over allied weapons; and

(ii) the enabling or, in [National Security Advisor Jake] Sullivan’s words, “force-multiplying” nature of the emerging technologies at issue.

In other words, the nature of today’s technological and industrial contest requires new assessments of both risks and contributors to national security.

Or as Wolf puts it more memorably, “The US is controlling the thing to make the thing to make the thing to make the thing that will give its military the advantage over ours.”

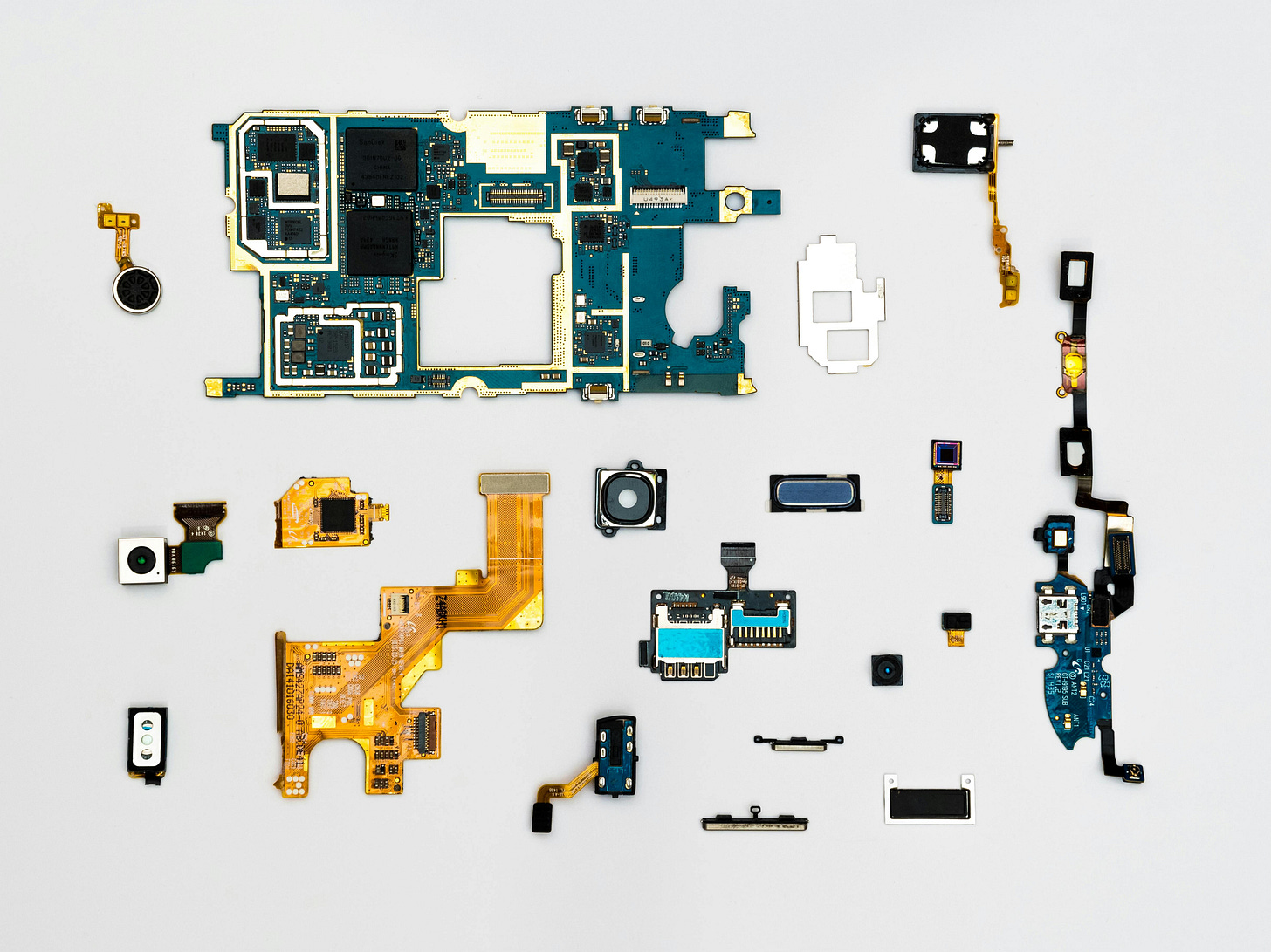

Instead of “just regulating the radiation-hardened chip that is necessary for a missile to function,” the new US export control regime targets the numerous technologies upstream of that missile. Wolf explains:

…the US is controlling the inputs for the indigenous development and production of the otherwise uncontrolled supercomputers needed to do the advanced designs to modernize the missile.

Then, moving my arm to the left, I say, the regulations control the types of semiconductors that are critical to the computers needed for designing the missile.

Then, moving my arm further left, the regulations are controlling the semiconductors that are needed to develop the AI- functionality the weapon will need to have quicker reaction times.

Then, still moving my arm to the left, the regulations also control the equipment and the items needed to produce the equipment that are needed to produce the semiconductors that are needed for the AI and computer applications that are needed to improve the weapon.

Then, in another arm movement to the left, I say they are then controlling the US person services that are needed to keep the tools running that are needed to produce the chip that is needed for the AI and computer applications that are needed to the do computer modeling to modernize the weapon.

Furthermore, BIS is sanctioning the Chinese companies that support the development and production of chips that create the AI- related and computer applications that are needed to modernize the missile.

China’s focus on industrial basics

While US policymakers are coming to realize that a secure industrial strategy starts at the upstream, China has long taken this whole-of-supply-chain approach.

And with it, Beijing has gained asymmetric advantage over numerous technologies.

Where the US has spent decades outsourcing everything but the most downstream, highest value-add segments of tech supply chains (“Designed in California, Made in China” is a canonical example), China has invested heavily in its industrial base.

It has long focused on building up its “industrial technology foundation,” referring to inputs like basic components and components, basic materials, basic manufacturing processes and equipment, industrial basic software.

That effort dates back to at least 2006, when Beijing, as part of a 15-year science and technology development plan, set a key goal of achieving breakthroughs in “core, high, and basic” tech: core electronic devices, high-end generic chips, and basic software.

China doubled down on basics in 2014 when it laid out measures to master the “four basics:” basic materials, basic parts, advanced basic processes, and industrial technology foundations (e.g. R&D, inspection and testing, technology standards). That effort continues apace.

One takeaway: Complex as the global industrial contest may be, it fundamentally requires going back to basics—in more ways than one.

Related:

Weekly Links Round-Up

🖇️ The risk of China’s nitrocellulose advantage – and what the US defense industrial base can do about it. China’s dominance in the input critical to making things that go bang “underscores is that trusted supply is necessary for competing with China,” write Emily de la Bruyère and Nathan Picarsic. (Force Distance Times)

🖇️ The Pentagon isn’t buying enough ammo. If “production is deterrence,” as the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment William LaPlante said last year, then the US isn’t currently doing a great job of discouraging would-be bad actors, argue Stacie Pettyjohn and Hannah Dennis. “The Pentagon needs to consistently buy more of the right weapons to support allies and partners, deal with the threats it faces today, and deter future challenges,” they write. (Foreign Policy)

🖇️ Texas-headquartered drone startup Anzu Robotics describes itself as “American-owned.” But as Kate Kelly reports, half of Anzu’s parts come from China and its drone designs are licensed from Chinese drone giant DJI. “That crossover is raising questions about whether Anzu is truly independent of DJI, China’s leading drone maker, or simply a rebranded version of it,” she writes. Meanwhile, DJI is funding a US-based “grassroots” industry group called the Drone Advocacy Alliance, raising questions about potential violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act. (New York Times, House Select Committee on China)

![Is [insert tech here] really the “latest front” in the US-China competition?](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!HL5X!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa3a7d210-660d-4978-86ba-12ddea62b499_6240x4160.jpeg)

My working hypothesis is that the US also needs to cultivate more high volume products (like the Tesla M3 and Y) to be assembled domestically.

Without these, is there an incentive for suppliers (and their suppliers) to build capacity domestically?

That the iPod/dumbphones and later the iPhone were assembled in China accelerated the strength their supply chain nodes and connections. And even reading that Reuters piece today, a larger portion of iPhones/smartphones are made by Chinese domestic competitors to chip and other component suppliers.

A less pronounced version of this has also happened with GigaShanghai.

So yes industrial foundations are important, but the US also needs to focus on fostering the industries where it is viable to build the world's highest volume and automation factories there.