Ammo, chips, and military upstream inputs

Production capacity even in relatively lagging-edge technologies can confer outsize strategic advantages—or costs.

Welcome to a/symmetric, published by Force Distance Times.

Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric.

In this week’s dispatch:

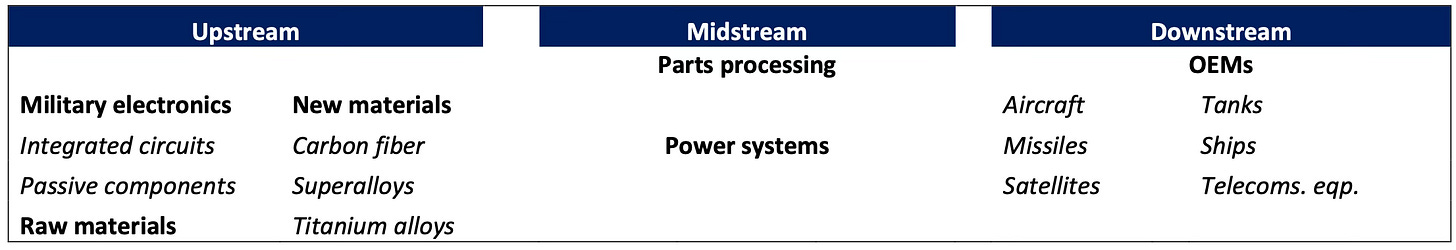

A look at two key upstream nodes of the military supply chain: chips and ammo

Weekly Links Round-Up

Ammo, microelectronics, and military upstream inputs

It was a big week for BAE Systems.

First, the British defense and aerospace group’s US subsidiary was awarded a 35 million USD federal grant under the CHIPS Act to quadruple its domestic production of military chips, including for use in fighter jets.

The next day, the Pentagon awarded the company a 10-year, 8.8 billion USD contract to continue making explosives at US Army’s main ammunition plant in Tennessee.

Officials said that tapping a military supplier, instead of a commercial chip maker, for the first ever CHIPS Act grant was aimed at underlining the government’s focus on national security.

There’s an even more important message: any secure industrial strategy—the linchpin of on national and economic security—starts at the upstream.

Exploiting the criticality of military upstream inputs

Both military chips and ammunitions, as critical upstream inputs, form the basis of military capabilities. To state the obvious: no chips means no satellites, stealth aircraft, and cruise missiles; no ammo means no ability to sustain a protracted war.

The outsize importance of military microelectronics and ammo also means that having sufficient manufacturing capacity of even relatively lagging-edge and lower-cost technologies can confer disproportionate strategic advantages—or, on the flip side, confer risks for critical dependencies on an adversary.

China understands this well. And it is capable of exploiting this asymmetry.

Low cost, high rewards

Take semiconductors. China continues to lag behind the most advanced silicon-based chipmaking technologies. But state planners and industry players alike recognize that achieving dominance in legacy chips can have huge payoffs, too, both for its domestic substitution efforts and its push to increase foreign dependence on Chinese supply chains.

China’s Great Wall Glory Securities writes in a recent report:

“Military chips do not actually have high performance requirements, but they have very high requirements for stability, reliability, and anti-interference capabilities in various complex geomagnetic environments…Although domestically produced…chips lack competitiveness in the civilian market, after transformation, they can not only promote the informatization of weapons and equipment in the military market, but also ensure chip security and controllability.”

That’s why, as early as 2007, Beijing launched a national science and technology initiative dubbed “core, high-end, basic:” to boost domestic capabilities in core electronics, high-end general-purpose chips, and basic software. By 2017, China had reportedly raised its self-sufficiency rate in core electronics from under 30% to above 85%.

As an author writing in the magazine Defence Industry Conversion in China notes:

“Due to the low difficulty of military chip technology development and the relative insensitivity to prices, it is believed that the localization of chips will achieve its first breakthrough in the military industry.”

In short: low cost, high rewards—a classic asymmetric play.

Big bang for the buck

The same goes for ammunition.

BAE Systems makes a range of explosives at the Holston Army Ammunition Plant. But the US is falling short on capacity to produce energetics, which are chemicals used to make explosives, pyrotechnics, and propellants. And the domestic energetics supply chain is reliant on raw material chemicals sourced from abroad, including China.

An interesting player in this space is Guangdong Hongda Holdings Group, China’s second-largest industrial explosives maker. The firm is a key node in China’s defense industrial complex: it’s a “military-civil fusion innovation demonstration enterprise,” and in 2018 it test fired its newly developed supersonic cruise missile. Hongda is also making investments in the upstream energetics space: just in September, it acquired Jiangsu Hongguang Chemical, a major manufacturer of the explosive compound RDX.

But we’ll get into all that another week.

Weekly Links Round-Up

China is ramping up its outbound manufacturing investment in Southeast Asian countries. As companies diversify their production beyond China, Chinese companies are also expanding operations overseas, partly to dodge US tariffs. Over 50 Chinese-listed firms have set up subsidiaries in Vietnam so far this year. AVIC Optoelectronics, for example, says its Vietnamese unit is a “resource pool” for key international customers.(WSJ, Shanghai Securities News)

“Reset, Prevent, Build:” The US House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party laid out nearly 150 policy recommendations for countering China and boosting US economic and technological competitiveness. The report highlights Beijing’s “intricate web of industrial policies” that disadvantage US firms and increase countries’ dependence on Chinese imports. One such industrial program is “little giants, single champions,” which we have researched extensively. Stay tuned as we continue to unspool more parts of China’s industrial policy web— and how they shape global business dynamics. (Washington Post, Force Distance Times)

The enduring risks of an everything shortage: we’ve put the worst of the pandemic’s supply chain disruptions behind us…or have we really? Companies appear to be reverting back to their just-in-time habits. “Structurally, nothing has really changed in the market from a supply standpoint,” as one economist tells Rachel Premack. (FreightWaves)