Over the past few decades, the comparative advantage theory would appear to have served the US and China pretty well. The story goes something like this.

Both countries got to specialize on what they were comparatively good at. The US designed iPhones; China assembled them. The US manufactured chips; China packaged and tested. The US developed drugs; China provided the raw pharmaceutical ingredients. Businesses maximized efficiencies and profits. Consumers accessed cheaper, more varied products. Plus, Washington wagered that China’s economic liberalization would eventually spill over to the political front.

But all along, the story was more complicated than appearances let on.

A lopsided game

While foreign countries readily offshored manufacturing to China in search of efficiency gains, Beijing saw a longer term opportunity to fast track its industrial development, leapfrog overseas competitors, and eventually eat their lunch. It did so by actively shielding the home market while showering state support on homegrown players to win market share abroad.

For example, foreign battery makers could set up factories in China—but they were blacklisted from state subsidies, so domestic manufacturers won the lion’s share of the home market. Foreign automakers could establish car plants in China, but must partner up and share know-how with local firms. Ditto for numerous other advanced industries: the carrot of selling to the vast Chinese market came with the stick of forced joint ventures and tech transfers.

As Robert Atkinson, founder and president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, wrote in a 2022 essay in Foreign Policy:

“China’s massive subsidies and other unfair practices used to build up advanced domestic industries...have nothing to do with comparative advantage. They reflect a desire for dominance through industrial predation: boosting their own firms while crushing foreign competitors’ ability to compete.”

All this takes place against the backdrop of China’s unbalanced economy and its distortionary effects on global trade.1 Jared Bernstein, chair of the US Council of Economic Advisers, gave an overview of this phenomenon in June:

“As economist Michael Pettis has long stressed, the true and powerful economics of comparative advantage are thwarted when countries don’t export to import, but export to build market share through economically large and persistent trade surpluses, matched by equally persistent current account deficits held by their trading partners.”

These asymmetries mean that even as China has carved itself key roles in global supply chains and made other countries dependent on its formidable manufacturing capacity, it continues to assiduously shield its relative independence.

In other words, China was de-risking long before the buzz phrase was coined. This creates a lopsided dynamic in which foreign firms’ short term profit motives directly buttress Beijing’s long term strategic goals.

“Comparative advantage is not a real advantage”

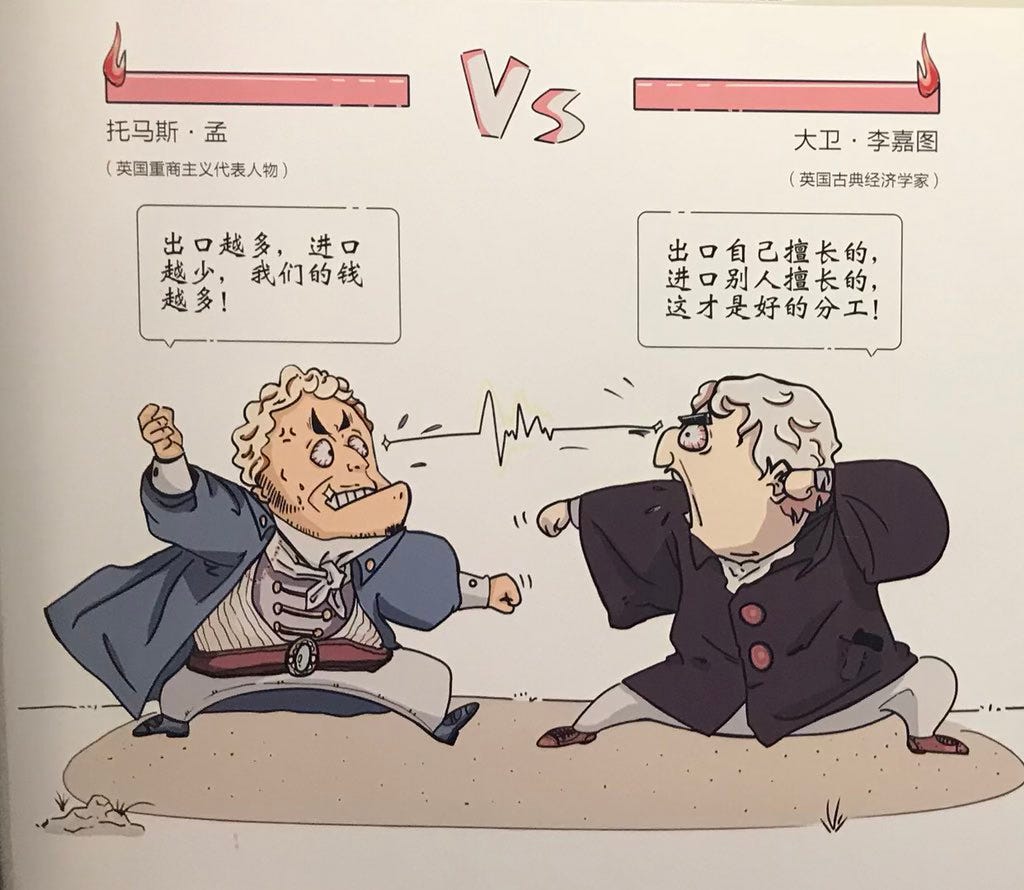

Chinese economists and analysts have publicly questioned the comparative advantage model.

While the theory has benefited China’s economic development in past decades, they say, transforming the country into a manufacturing superpower requires rethinking the orthodoxy of comparative advantage. That’s the economic theory that a country should focus on producing what it’s comparatively best at, and import the rest.

But, according to some critics of the theory, treating comparative advantage as gospel prevents China from moving up value chains and pushing the frontiers of technology. That’s not to reject the theory completely, but to acknowledge its limitations. After all, if it’s assumed that Apple’s strength will always be designing brilliant products while China’s is to supply and assemble the components, why would China try its hand at developing iPhone competitors?

A prominent corporate strategy expert put it this way in a 2007 essay published in state media:

“Advantage is not a winning position, and comparative advantage is not a real advantage…This comparative advantage is only a temporary advantage for a certain time, a certain matter, or a certain aspect. This advantage is not static and can be transformed into a winning position. If it is well played and used, it can become a winning position. On the contrary, the advantage may also become a disadvantage.”

Rather than rely on comparative advantages, China should “actively cultivate potential technical advantages,” notes a 2019 essay in the Chinese Communist Party’s leading theoretical journal. And those competitive advantages can change over time. Pei Changhong, the director of the Institute of Economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, illustrated this point with the following chart in a recent paper:

The idea is that new advantages can be honed and leveraged at different stages of development. For example, low wages were once China’s most salient advantage. But rising labor costs eventually marked the end of cheap Chinese labor. China’s edge would now have to be found elsewhere: its deep industrial base that makes possible vibrant process innovation, for instance, and a vast market to roll out technologies at scale.

Another industrial economics expert dubs this the theory of “dynamic competitive advantage.” To cultivate Chinese global champions across key industries, he writes, China should:

“...actively abandon certain economic theories of the past, such as not implementing the so-called ‘play up strengths and avoid weaknesses’ strategy guided by the theory of static comparative advantage, and giving up on catching up or investing in certain upstream segments of [global value chains] that are highly knowledge- and technology- intensive. Instead, we should be guided by the theory of dynamic competitive advantage, implement the strategy of ‘building on our strengths to make up for our weaknesses’, and make every effort to widen development bottlenecks.”

Lessons for the US and Europe

All this raises questions for how Washington and Brussels approach technological and industrial competitiveness.

For years, the US outsourced manufacturing to China. Europe did too, and in addition outsourced its energy needs to Russia. But as Mario Draghi put it in a landmark report on EU competitiveness published this week, “our dependencies have turned out to be vulnerabilities.”

The challenge now is patching those weaknesses while clawing back existing comparative advantages and fostering new ones. The flood of cheap exports from China only complicates that task.

The US, for one, remains a font of cutting edge innovations; its launch of industry leading large language models is a case in point. Now it needs to translate that first-mover advantage into enduring industrial competitiveness. Meanwhile, “the EU’s comparative advantage in green technologies is increasingly challenged,” says Draghi, and it will have to buckle down to retain it.

Those aren’t easy tasks. Comparative advantage works well in a world of free and fair trade. When those presumed conditions are undermined, there emerges a fissure between theory and reality, in turn spawning economic and national security risks.

The resurgence of US industrial policy, as signaled by the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act, offers one way to “generate new areas of comparative advantage.”2 But perhaps the most important comparative advantage of all, and that any well-designed industrial policy should reinforce, is the dynamism of the US free market economy. That’s something that China will struggle to crack for a long while yet.

Thank you to Shreeda Sagan, Rob Tracinski, and Rob L’Heureux for their feedback.

For a longer treatment of this thesis, see Trade Wars Are Class Wars (2020), by Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein.

As the economist Dani Rodrik phrased it in his 2004 paper, “Industrial policy for the Twenty-First Century.”

As long as we keep listening to hostile Western China experts like the ever-wrong Michael Pettis, we keep drifting towards irrelevance. Let us count the ways:

1. China’s massive subsidies and other unfair practices? Massive subsidies are unfair in competitors' eyes. See the billions in subsidies that continue pouring into Boeing-Airbus and a thousand 'strategic' industries.

2. "China’s unbalanced economy"? We know that China's economy is growing for the same reason we know a sprinter is accelerating: imbalance is an essential aspect of growth. Europe's economy is balanced. It's also dying.

3. "China’s edge would now have to be found elsewhere: its deep industrial base?" China's edge is, has always been and will remain its 6-point advantage in median IQ over us and its 1500-year habit of allowing only men with IQs above 140 (enough for a PhD in theoretical physics) with uncommon energy and integrity to govern. Even the average Beijinger enjoys a 10 point advantage over, is much healthier and more energetic, and will live 10 years longer than the average Washingtonian.

3. "The US, for one, remains a font of cutting edge innovations; its launch of industry leading large language models is a case in point"? LLMs have yet to contribute anything real to the economy. Outside the VC hoopla, China is so far ahead of the US in every scientific discipline that the competition is essentially over. Seven of the world's top ten research institutions are Chinese. One is American.

4. “the EU’s comparative advantage in green technologies is increasingly challenged"? If it ever had an edge, Europe has none now. 70% of indigenously produced 'European' wind generators comes from China, as do 90% of its solar panels. And China is two generations ahead of the world, ex-Russia, in nuclear power.

The author has addressed some important points, but Fox News headlines are not a useful basis for doing so.

The theory of comparative advantage simply ignores the role of learning; it’s perfectly legitimate for a developing country seeking to move to the technology frontier to subsidise learning and knowledge acquisition by its own population. In fact, that’s what we do as individuals. Our parents subsidise our learning activities, so we become more productive later in our lives.