China is exporting its entire EV industrial chain

Car exports are a function of a larger strategic goal: “whole industrial chain output"

Welcome to a/symmetric, published by Force Distance Times. Each week, we bring you news and analysis on the global industrial contest, where production is power and competition is (often) asymmetric.

This week:

China is exporting its entire EV industrial chain. The automotive story goes beyond unit sales. Car exports are a function of a larger strategic goal: “whole industrial chain output,” which can in turn be leveraged to win influence over global commerce.

Weekly links round-up: Apple and Huawei took different bets on EVs, Silicon Valley bets on hypersonics, Japan and arms exports, and the 6G competitive battlefield.

China is exporting its entire EV industrial chain

The China EV narrative you’re probably most familiar with is the country's surging EV exports, which grew 64% last year.

Car exports are certainly part of the story. But the broader narrative goes far beyond unit sales. Car exports are a function of a larger strategic goal: exporting China’s EV industrial chain.

A recent article in Securities Daily on the changing competitive landscape for autos makes this succinctly:

“Product export is the form, and the business model is the essence. The significance of cars going overseas goes far beyond car sales themselves. In addition to bringing out products and industrial chains, it also involves a wide range of services, management models, trade logistics, cultural exchanges, and even the display of national image.”

In other words, China’s EV exports are a step towards an even greater prize: more influence over industrial chains, technology standards, trade flows, business models, and global commerce writ large. That in turn further complicates US efforts—like the investigation launched this week—to check possible national security risks from foreign-made EV components and software.

There’s also a larger point to all this. Assessing how China competes in strategic industries requires understanding what metrics are used and prioritized. Those metrics often differ, whether in kind or in relative importance, from those that guide Wall Street. Think: market share and leverage over key supply chain nodes,versus quarterly profits and losses.1 This is a generalization, of course. But it’s a point worth keeping in mind when thinking about, say, Chinese EV exports—and whether more sales is the end goal, or a means to a larger strategic objective.

A state-led automotive full court press

Little wonder, then, that the Chinese government—at both national and local levels—is leading a coordinated and comprehensive push to export and expand various segments of the EV supply chain.

Shenzhen this week unveiled a plan to support car exports, including measures to speed up export license approvals, opening new shipping routes, offering tax refunds and export credit insurance, and building overseas factories and R&D centers.

The measures are much like those proposed by the Chinese ministry of commerce last month, which called for the “healthy development” of automotive trade, largely through government-directed coordination to juice Chinese EV makers’ competitiveness overseas. They also echo directives from the State Council last year, which among other things called for state-led matchmaking between car makers and shipping companies.

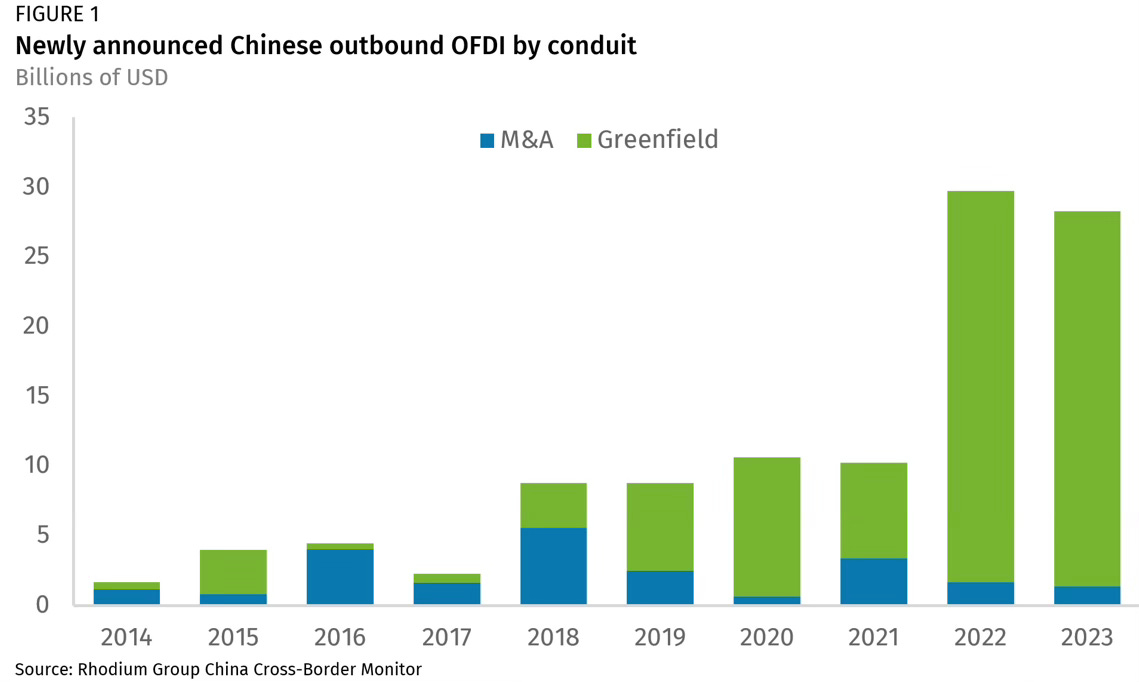

The effects of these policies are already being reflected in data. According to Rhodium Group, China’s new EV overseas foreign direct investment last year hit $28.2 billion, and was overwhelmingly driven by greenfield investments. Or as a top Chinese government agency put it, “More and more Chinese car companies are not stopping at ‘products going overseas,’ but are moving towards ‘manufacturing going overseas.’”

In short, the Chinese government is putting its full weight behind not just exporting cars, but what the vice chairman of the China’s top EV think tank calls “whole industrial chain output.”

What “whole industrial chain output” looks like

Recent developments give us an idea of what Chinese EVs’ “whole industrial chain output” looks like:

BYD is reportedly in talks with Italy about potentially setting up a second European plant there. BYD’s first plant on the continent will be in Hungary—no doubt with an eye to avoiding potential punitive tariffs levied by Brussels. And BYD is eying a plant in Mexico, too, in an attempt to dodge US tariffs.

Fiat maker Stellantis, which last year bought a 21% stake in Chinese EV maker Leapmotor, is considering building Leapmotor EVs in Italy—in a historic Fiat plant, no less.

US automotive supplier BorgWarner inked a deal with BYD’s battery subsidiary, FinDreams. The US firm will manufacture EV battery packs using components from its Chinese partner.

The tie-up shares similarities with the controversial Ford-CATL partnership, in which the US carmaker would license technology from the Chinese battery giant to build a EV battery plant in Michigan. In both instances, neither BYD nor CATL increases their physical footprint in the US, but their technologies become more deeply embedded in US automotive supply chains.

Driving these various developments is China’s desire to leverage dominance in EVs and batteries to counter geopolitical headwinds and sidestep (or undermine) trade barriers.

Zhang Monan, researcher at China Center for International Economic Exchange, boils down the strategy for doing so to two steps: increase “strategic mutual dependency” between China and the west; and leverage open markets to counter the US and EU’s de-risking efforts.

So far, it looks like that strategy is bearing fruit.

Weekly Links Round-Up

🖇️ Silicon Valley bets on hypersonic weapons. Venture capitalists “are now deploying hundreds of millions of dollars into developing the technology for hypersonic weapons the US military wants but has struggled to figure out despite decades of trying,” reports Heather Sommerville. Still, while sophisticated missiles are nice to have, having a robust defense industrial base to ensure supply upstream inputs like energetics and military chips is just as important, as we’ve written in previous issues of this newsletter. (WSJ, a/symmetric)

🖇️ Apple and Huawei took different bets on cars. And now the Apple car is dead. For Quartz, I wrote about the two tech firms’ different EV strategies, and how Huawei’s approach reflects its belief that EVs are one part of the broader industrial internet—for which the company wants to be the dominant platform player. (Quartz)

🖇️ Could Japan fully lift its arms export ban? The country’s former national security advisor floated the idea in an interview, noting that Tokyo is now facing the “toughest and most complicated" security challenges in the postwar era. He added that expanding arms exports could boost the domestic defense industrial base. (Nikkei Asia)

🖇️ Gearing up for the 6G competition. The US and its allies unveiled shared principles to guide work on 6G communications systems, including ensuring that they are “open, free, global…and secure.” Meanwhile, China has already spent years building up its 6G capabilities: Chinese telecom equipment makers saw their shares pop double-digit percentages on news of the joint statement. Plus, for a primer on current state of the 6G competition, see this report published in September. (Axios, WSJ, Hinrich Foundation)

China’s “single champions” industrial program, for example, explicitly prioritizes market share—and the leverage over key value chains that comes with it.

Excellent piece. China has a very clear strategic path on EVs