The cutting edge is prized as the frontier of human knowledge and technical capabilities. And for good reason.

Without cutting edge technology, we would not have had mRNA vaccines against Covid, nor synthetic fertilizer that fueled the green revolution, nor the steam engine that powered the industrial revolution, nor the semiconductor that heralded the digital revolution.

But plenty of innovation happens at the dull edge, too. Reassembling old tech in new ways can cut costs, skirt technical bottlenecks, and sidestep trade restrictions. Old tech is also tried, tested, and reliable. Old wine in new bottles needn’t be pejorative, but genuinely innovative.

That’s welcome news for latecomers like China working to catch up with forerunners like the US. And the corollary is that incumbent leaders risk being outflanked if they try to maintain their primacy by overly focusing on the cutting edge.

China is spreading its bets. It is pouring money into future industries with the hope of winning a coveted, lucrative spot on the frontier. It is also investing in technologies within the frontier.

“We usually think that so-called new technologies are necessarily brand new technologies, but that is not the case,” wrote Renmin University economist He Fan in a 2017 essay. “New technologies are often the combination of existing technologies in a new form.” He calls this “poor man’s innovation.”

“Poor man’s innovation”

One example of this pauper’s approach to new ideas is China’s push to develop chiplets.

Chiplets are an emerging technology, but they create new opportunities for older tech. Think of chiplets as Legos: smaller chips are packaged together as one, allowing a mix-and-match of both leading and mature components.

“By connecting several less-advanced chips into one, Chinese companies could circumvent the sanctions set by the US government,” journalist Zeyi Yang reported in MIT Tech Review earlier this year. “…If China can’t buy or make a single piece of a powerful chip, it could connect some less-advanced chiplets that it does have the ability to make.”

Chiplets may even play to China’s strengths. As the business outlet 21 Jingji notes, the process of combining and stacking chips at root relies on packaging technology, “and China accounts for a quarter of the global chip packaging and testing market.”

Huawei is among those betting on chiplets. In 2022, an executive said the company was adjusting its strategy to leveraging surface area and vertical stacking to squeeze additional performance. “Not-so-advanced processes can also achieve good results,” he said at that year’s earnings conference.

The Chinese government is similarly eager to exploit the chiplet workaround. According to Reuters, Chinese authorities hardly mentioned chiplets before 2021, but have since elevated them to a key position within China’s technology strategy. It’s even cultivating a “Chiplet Valley” in the city of Wuxi.

That effort is already showing results. Last spring, China put in place its first state-approved industry standards for chiplets and optical chiplets, signalling Beijing’s intent to shape the protocols of this new technology. And following a recent breakthrough in domestic chiplets, the state-run Reference News touted the development as “an important path towards breaking the US technology embargo.”

Nintendo and “withered technology”

Innovating on the lagging edge can also pay off handsomely. Just ask Nintendo.

In the spring of 1989, the Japanese company unveiled a gray brick with a tiny monochrome screen. It was the Game Boy, and it would revolutionize portable handheld gaming.

Yet the console was no technical powerhouse. It was powered by a custom chip that was very similar to the Intel 8080 and Zilog Z80, chips that had been launched more than a decade earlier. Its screen was black and white at a time when competitors were already working on color displays. And, well, the display also had an ugly green tint.

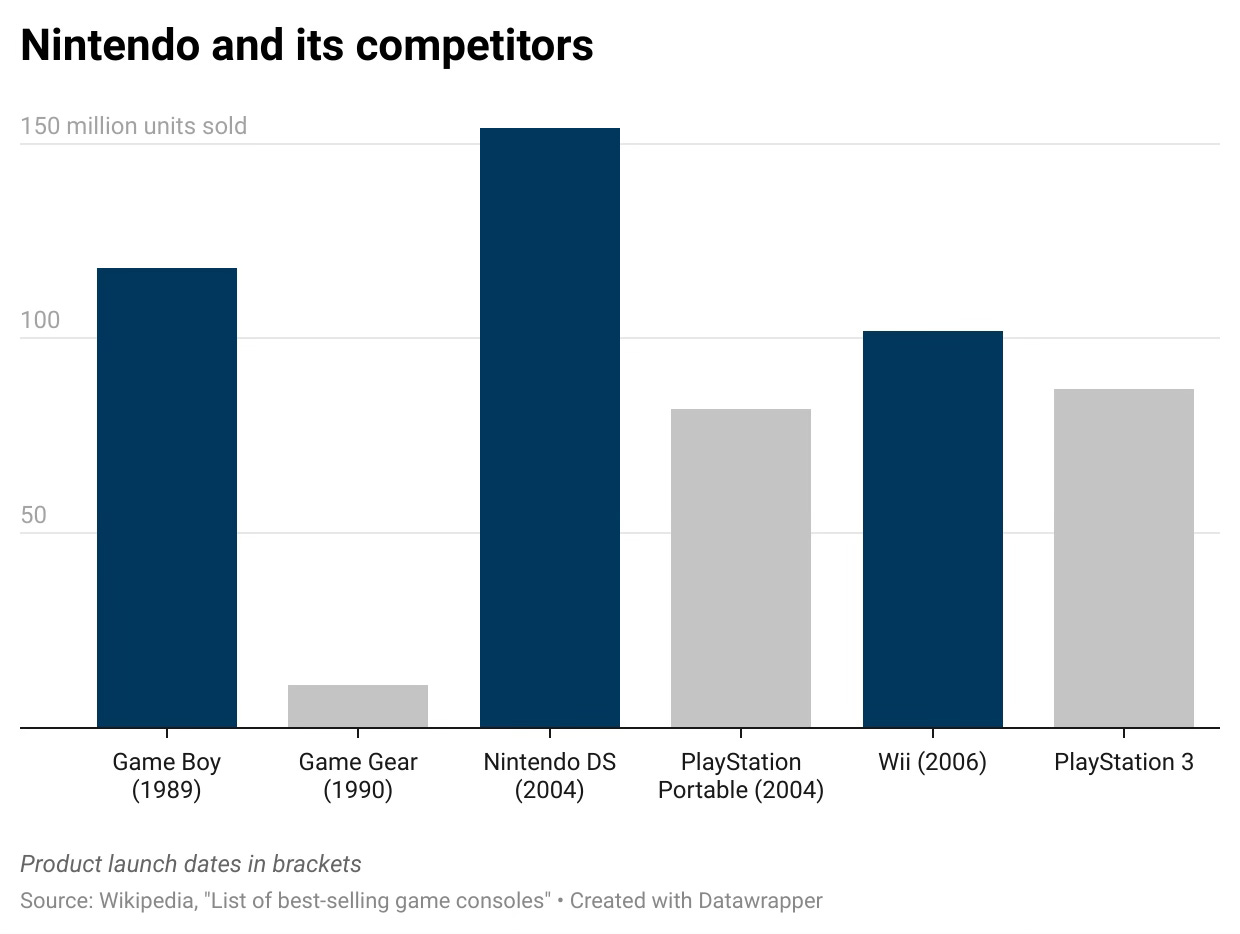

Still, the Game Boy was a hit, blowing rival products out of the water. It was sturdy, reliable, and cheap. It was power efficient. And it was easy to use, having replicated a tried-and-tested controller design that had already been launched several years earlier. The Game Boy went on to sell an estimated 118 million units. The flashier full-color Game Gear by Sega, which launched in 1990, sold 11 million units.

Longtime Nintendo employee Gunpei Yokoi, who is credited as the creator of Game Boy, dubbed his design philosophy “Lateral Thinking of Withered Technology:” using cheaper, older technology to create compelling products on sturdy foundations. This strategy would continue to serve Nintendo well with the Nintendo DS, Wii, and Switch.

The lessons from Nintendo’s success aren’t lost on Chinese academics and industry observers, who see in the Japanese video game maker a reminder that groundbreaking innovations can stand on the shoulders of old technology.

Plus, the implications of runaway product sales go beyond fat revenue streams. As a dominant player, Nintendo is able to “link up the game industry chain and build a game industry ecosystem,” says Li Haigang, a professor at Shanghai Jiaotong University’s economics and management school. This gives Nintendo immense market power, and strengthens associated suppliers and game developers—a dynamic that China’s industrial strategy consistently aims for.

Old parts, new assembly

Sometimes, the parts required for new inventions are right under our noses. Case in point: the intermittent windshield wiper.

In 1963, mechanical engineer Robert Kearns developed the contraption by rearranging already existing basic circuit components: a transistor (invented in 1947); a capacitor (whose origins date to the 1740s); and a variable resistor (first developed in 1841).

A 1993 New Yorker article described the intermittent wiper’s operation:

“Kearns’ intermittent wiper was an elegant piece of engineering…The resistor and the capacitor together were the timer, and the transistor worked as the switch. The resistor, which the driver could adjust with a knob, controlled the rate of current flowing into the capacitor. When the voltage in the capacitor reached a certain level, it triggered the transistor; the transistor turned on, and the wipers wiped once. The running of the wiper motor drained voltage out of the capacitor; it sank below the threshold level of the transistor, and the transistor turned off. The wipers dwelled until the capacitor recharged.”

The product was so compelling that, as Kearns alleged, Ford stole the idea from him. A 12-year-long legal battle ensued, eventually ending in a settlement with Ford for $10.2 million.

What chiplets, Game Boys, and intermittent wipers share in common is that they all use existing (and, some might say, inferior or obsolete) technology to bring forth novel, innovative applications, or to get around constraints.

To be clear, this is not an argument against doing crucial, frontier pushing research. But innovation has many dimensions. While cutting edge breakthroughs may be the most visible barometers of technological advancement, the quieter workhorses of “withered” technology can beat new paths to progress.

China, out of foresight and necessity, is leveraging technologies old and new in its bid to catch up to and supersede the US. And America is no stranger to the value of new concoctions from old ingredients: intermittent wipers underline this, as do the many Apple products that repurposed existing components in exciting new ways. For anyone following the global industrial contest, it pays to keep a finger on both cutting and dull edges.

Thank you to Rob Tracinski, Quade Macdonald, Rob L’Heureux, Jeff Fong, Rosie Campbell and Steve Newman for their feedback on earlier drafts.

Weekly Links

🖇️ IBM shuts its China R&D operations. Big Blue’s retreat is due in part of rising geopolitical tensions, and comes a few months after Microsoft asked hundreds of its China-based AI and cloud computing staff to consider relocating to other countries. (WSJ, Rest of World)

🖇️ “Vertical Integrators will be the biggest winners of the Techno-Industrial Revolution,” writes Packy McCormick. Where a deep tech firm “designs a product for optimal performance…a Vertical Integrator designs a systemfor optimal performance.” The latter is a playbook that China knows well. (Not Boring, a/symmetric)

🖇️ Chinese airlines muscle in on major international routes. “This year, Chinese carriers are expected to supply 63% of the seats on flights to the mainland,” up 10% from pre-Covid. Chinese carriers are pricing aggressively, and foreign airlines have to contend with the added pressure of lower demand to visit China. (Bloomberg)

Very interesting stuff about chiplets. What are the downsides of them? I would assume they run into interconnectivity issues. I wonder how their efficiency compares at different sizes.

Leading-edge and trailing-edge engineers could be described as hot competitors, right now, for years, in batteries.

"Leading edge" would surely be a new breakthrough battery chemistry and design that throws Lithium-Ion into the shade, where "Nickel-Cadmium" now dwells - haven't seen a "Ni-CAD" in years.

"Trailing edge" would just be picking away at the efficiency of manufacture of the current battery, now >30 years old.

And, for years now, Li-Ion has been getting cheaper, faster than they can ramp up leading-edge would-be replacements into its competition space.

Trailing edge is undoubtedly more of the economy, for instance:

Internal combustion engines got 30% more efficient, the last 50 years since the 1973 oil crisis.

The improvement was obscured by people taking that brilliance, and using it to buy giant SUV and Trucks, rather than save gas...but arguably it created the new product category; an SUV would be much more gas-expensive and have lower sales.

In my own job, PVC plastic for water pipe didn't change the industry or anything, but it costs half what ductile iron did, can be moved around in the trench by one guy instead of needing a backhoe, halving construction effort ... and it NEVER corrodes, eliminated literally millions of main breaks over 40 years now.

Just one of a thousand things that get better every year with almost nobody outside the given industry, even knowing about it.