The idea of technological “chokepoints” lurched to the forefront of the Chinese collective imagination half a decade ago when Washington slapped sanctions on two Chinese tech giants, cutting their access to US technology overnight.

The “ZTE incident” and “Huawei incident,” as the 2018 and 2019 episodes are known, forced a reckoning across Chinese industry and government: dependence on a geopolitical rival had grown so acute that a flick of a pen from halfway around the world could, at least temporarily, cripple two domestic technological crown jewels.

China went into overdrive to uncover and dismantle latent chokepoints and prevent new ones from forming. Beijing set up a national technology security system to better protect its high-tech firms. The government’s main science funding body launched an emergency project to study and solve the “chokepoint problem.” And state media published a list of 35 chokepoint technologies on which China urgently needed to reduce its foreign dependence.

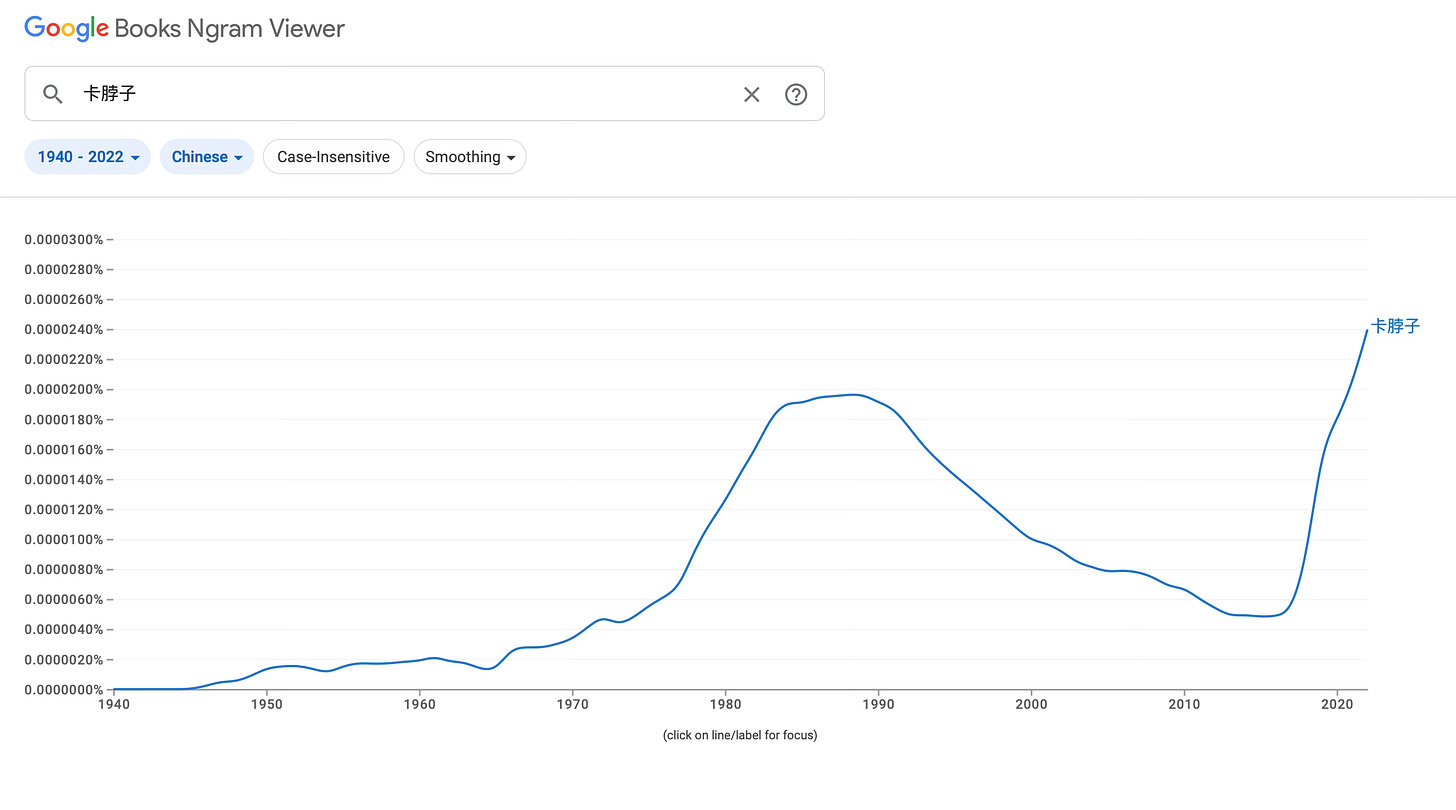

Today, talk of chokepoints (or chokeholds, “卡脖子”) continues to shape discussions on China’s technological development. The concept represents both risk and opportunity: critical dependencies can hobble Chinese industry, but conversely China can put other countries in a stranglehold by threatening to withhold certain materials or technology.

Chokeholds are no fun. But in an era of criss-crossing supply chains and rising geopolitical temperatures, great power contests could well turn on who can best deploy and deflect chokeholds at critical moments. And that requires a clear understanding of what makes and breaks chokeholds.

What makes a chokepoint technology?

For how much they figure in Chinese discourse, chokepoint technologies are fuzzily defined. Broadly, they are technologies where China is dependent on foreign companies for key components, equipment, or know-how. Cutting-edge semiconductors are a prime example due to China’s dependence on Dutch lithography machines and American advanced chip design software.

Some Chinese industry experts think the chokepoint idea is prone to overdiagnosis. Its catchy framing and vague definition may be to blame. That has implications for how resources are used and investments directed, with potentially high opportunity costs of chasing the wrong breakthrough.

That risk also applies to the US: Washington is increasingly aware of Beijing’s chokeholds on it, but is still iterating on a coherent strategy for restricting China’s access to its advanced tech while reinforcing its own capabilities and strengths.

Ballpoints and chokepoints

The humble ballpoint pen is a cautionary tale.

China has long been dependent on imports of the tiny steel ball bearings that dispense ink from pen to paper. Beijing didn’t like that. In 2011, the science and technology ministry launched a national research project aimed at developing and industrializing “key materials and preparation technologies for the pen manufacturing industry.”

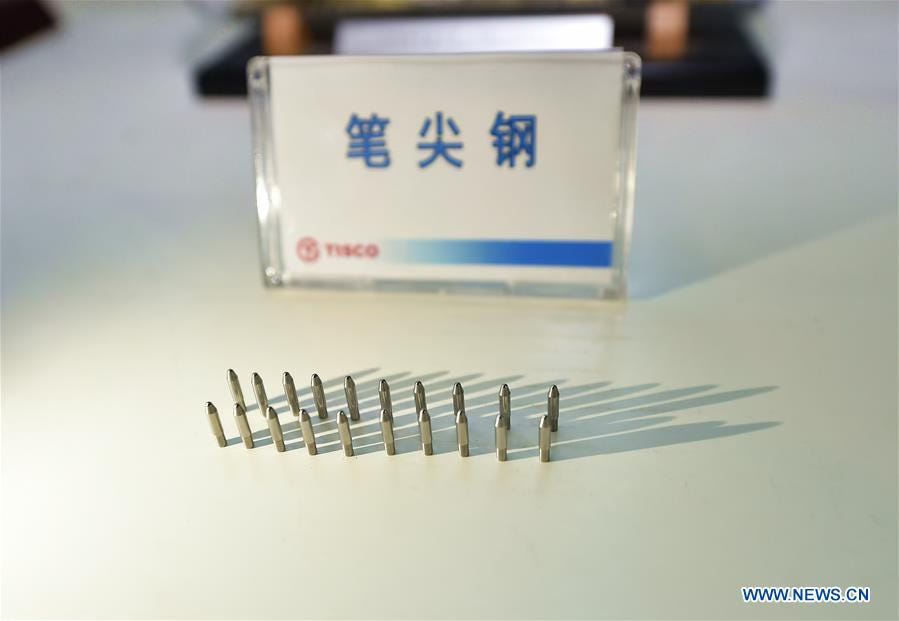

State-owned steelmaker Taiyuan Iron and Steel (TISCO) got the memo and got to work. Five years and 60 million yuan in state funding later, it declared success. Domestically made 2.3mm ballpoint pen tips began rolling off factory lines. TISCO’s shares jumped nearly 30%.

Chokepoint unblocked and chokehold broken? Not quite.

Today, China is still reportedly 80% dependent on imported ballpoints. Though TISCO did notch a technical breakthrough, domestic ballpoint pen manufacturers were reluctant to use the China-made ballpoint pen tips. The new steel balls didn’t work well with existing Swiss precision machine tools. They were not readily compatible with imported Japanese and German ink. And it made little economic sense for domestic steel mills to set up a new production line for such a tiny output of ballpoint tips.

In short, China made an isolated technical breakthrough on ballpoint tips that was of little use to the broader Chinese industrial system.

Pinpointing a systemic problem

Semantically, chokepoint implies a single point of dependence and failure.

But as the ballpoint pen story above illustrates, fixing a chokepoint requires far more than making a single breakthrough. Any solution has to be congruent with the existing network of suppliers and manufacturers, and their incentives, cost structures, and business models.

“The chokpoint problem involves the intersection of multiple supply chains and multiple nodes. It is extremely difficult to exhaust the problems simply from one industry or one industrial category,” writes Chinese industry expert Lin Xueping in his book, Supply Chain Attack and Defense.

“To tackle the problem, it is far from enough to just list the chokepoints,” he adds. “Chokpoint products are just the tip of the iceberg. Their underlying related factors below water can only be detected if there is a systemic understanding.”

There’s a larger industrial policy lesson here. Certain strategic and emerging industries require government prodding to kickstart, attain viability, or retain. But there are also lots of technologies where the market will always know far more than technocrats; just look at China’s wasteful ballpoint pen foray. The first step to breaking chokeholds is sorting out the real ones from the fake outs.

Weekly Links

🖇️ The political economy of making cars. Charles Yang has an incisive analysis on the US auto industry, its innovator’s dilemma, and implications for how it fares in the face of domineering competition from Chinese EVs. (Rought Draft)

🖇️ Chinese firms are setting up “back doors” to global markets. To evade tariffs, barriers, and scrutiny, Chinese companies are operating and investing via entities registered in non-aligned third countries like Singapore, Vietnam, and Hungary. a/symmetric got a small shoutout in the article, drawing on our earlier piece about a Singapore-registered Chinese firm’s attempt to covertly takeover an Aussie miner. (Financial Times)

🖇️ The bear case for Tesla robotaxis. “Chinese competition is poised to take the bulk of the global EV market with their super-cheap vehicles. Tesla needs to compete against that; its decision to prioritize robotaxis over a cheap ‘Model 2’ EV would seem to be an admission that they think they can't,” writes innovative mobility consultant Andrew Miller. “And if indeed they cannot compete against Chinese opponents, then Tesla can't afford the gestation time that robotaxis require. (Changing Lanes)

What’s the purpose of state media communicating out the choke point report you mentioned?

My mental model here is that the party comes to some policy consensus at the elite level, behind closed doors (and then implementation is a tops down process). Maybe my undergrad comp pol class framework is out of date?

I love how the term 卡脖子 used to be machine translated as “stuck neck”