This week:

Industries of the future: And how China is positioning to dominate them.

Weekly Links: Clean energy innovation., tade barrier workarounds, and Japan’s China dependence rises.

Back to the future industries

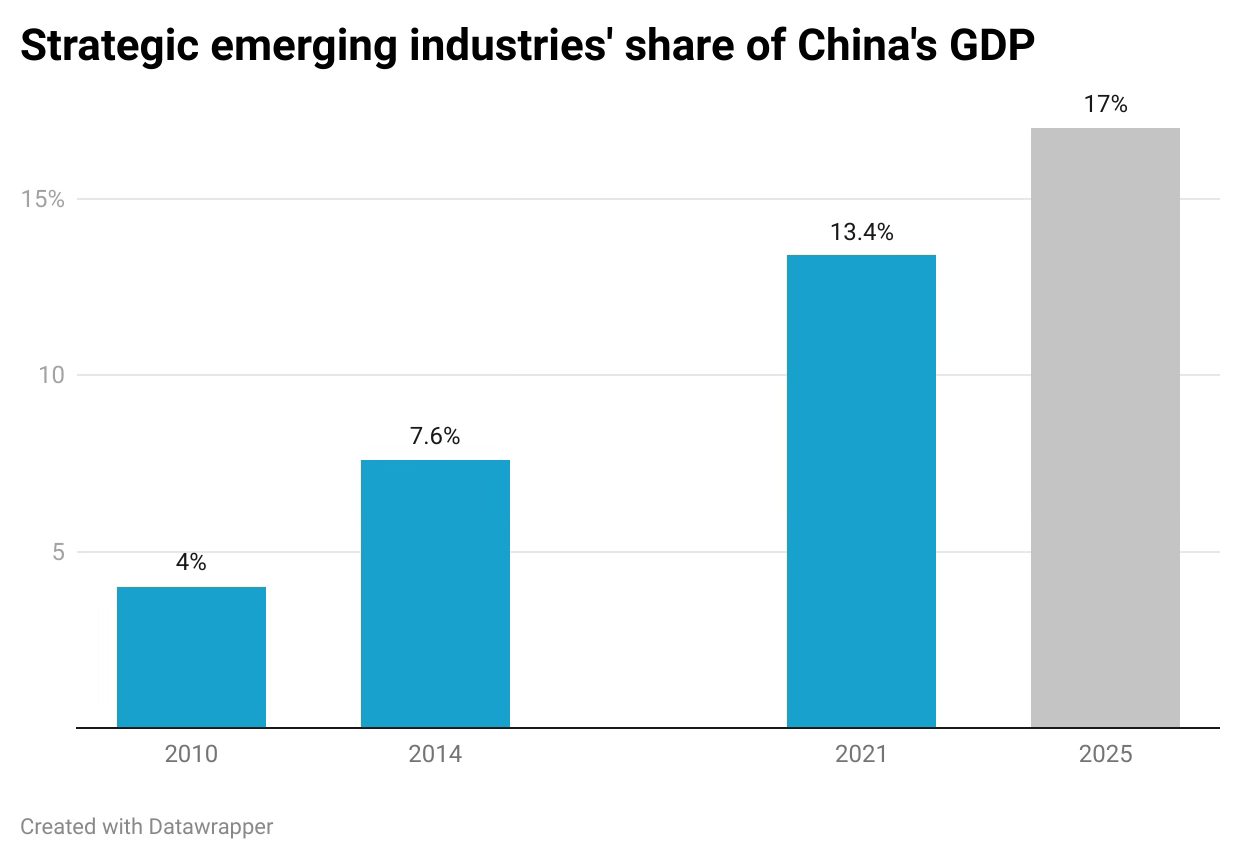

In 2010, as the world was still reeling from the Global Financial Crisis, China launched a new industrial policy: the Strategic Emerging Industries program. The initiative selected seven technology domains of “great strategic significance,” targeting them with extensive state support.

Two dozen years on, what was emergent then has today become more established — with China firmly entrenched in dominant positions in some of the technologies it had shortlisted.

Now, China is turning its attention to a new set of domains: “future industries.”

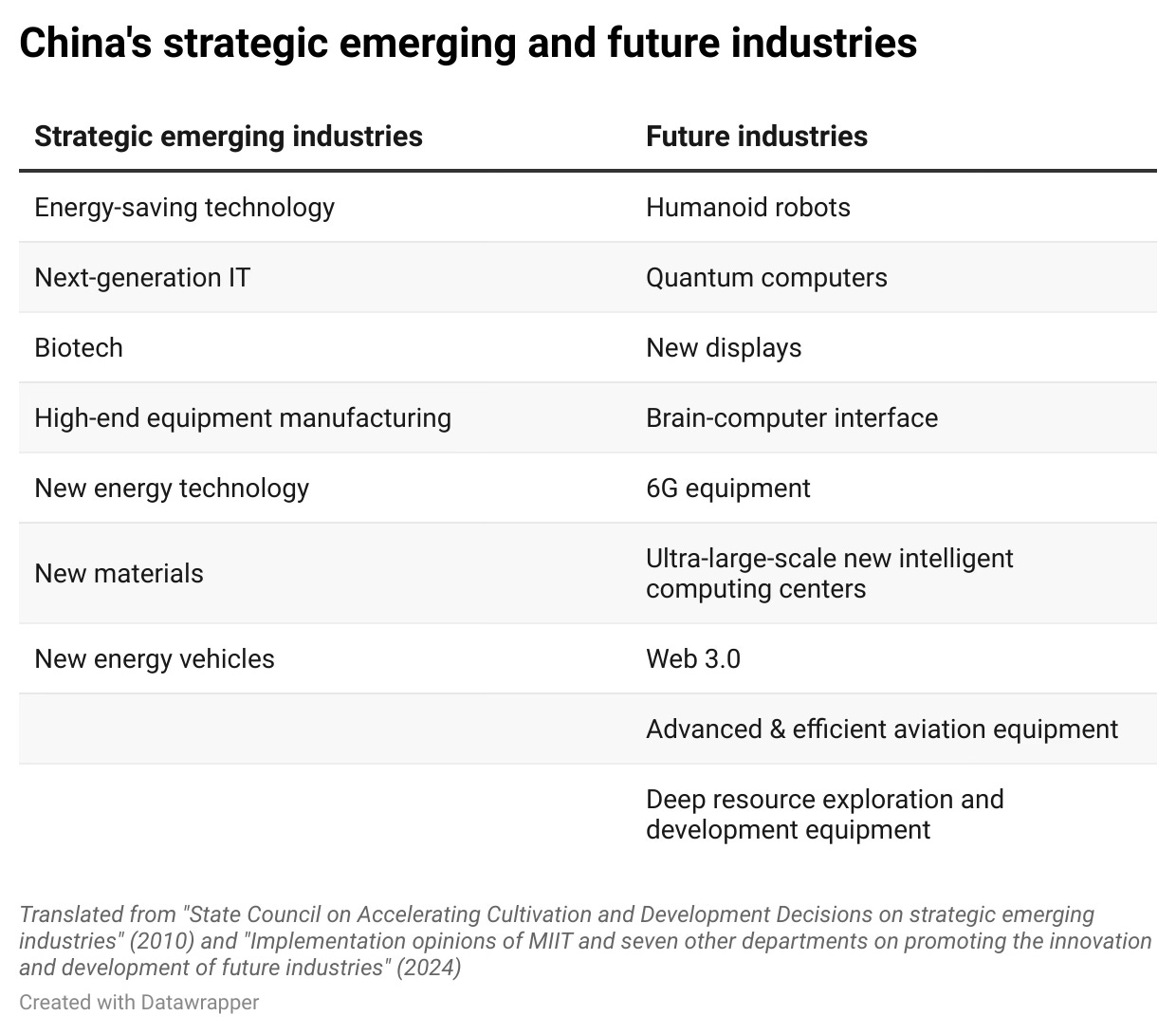

Beijing defines future industries as those “driven by cutting-edge technologies, are currently in the incubation stage or at the beginning of industrialization… with significant strategic, leading, disruptive, and uncertain characteristics.” It has already identified 10 such future industries (see table below).

Of course, future industries are moving targets: today’s future is tomorrow’s present. But if China’s current dominance in EVs, batteries, wind, and solar is any guide, its ability to invest in and stake out advantageous positions along key industrial chains can pay off handsomely in both commercial and strategic dividends — with vast national and economic security implications for its competitors.

And China is clear-eyed about the stakes.

“Looking back on the past, the strategic emerging industries of the past were also the future industries at that time,” state media wrote in March. “…The strategic emerging industries represented by the ‘new three’ [batteries, EVs, solar panels] have ‘overtaken on the bend’ because they grasped the future at that time. Developing future industries is to continue to compete for the future.”

How China is maneuvering to dominate future industries

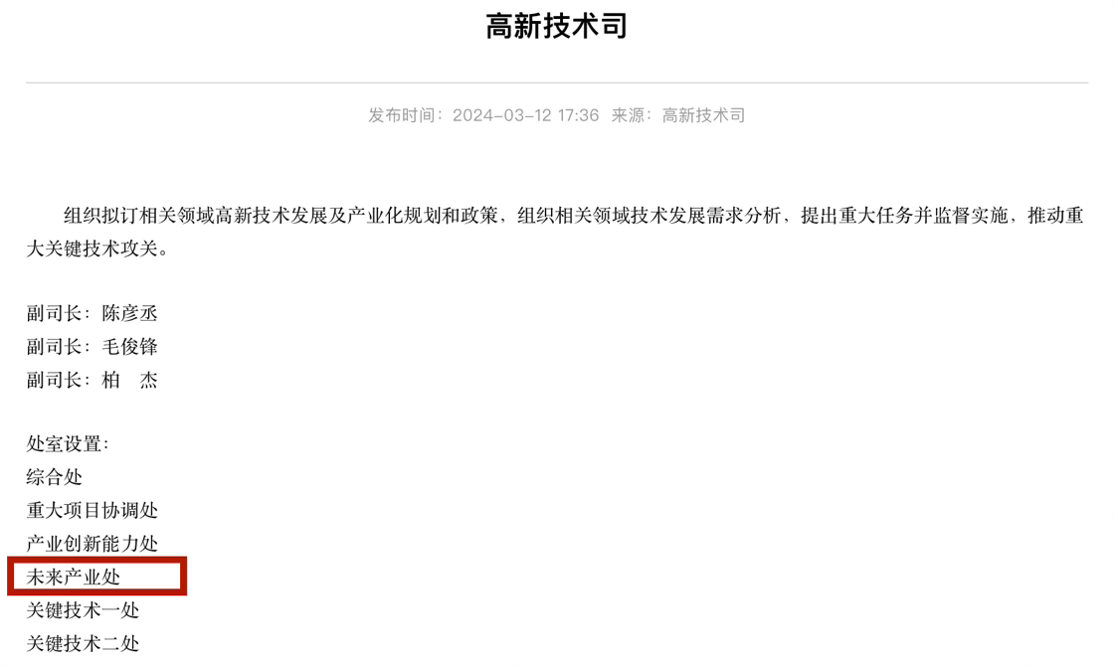

Here’s an indication of how seriously Beijing is taking future industries: in the spring, MIIT set up a new Future Industries division within its existing Department of High and New Technology.

As state media noted at the time, this marks the first time a national-level ministry has set up a dedicated body for future industries, and “means that the future industry has entered the national industrial layout plan.” In other words, future industries are a matter of national strategy, and will most likely be given the resources and attention to match.

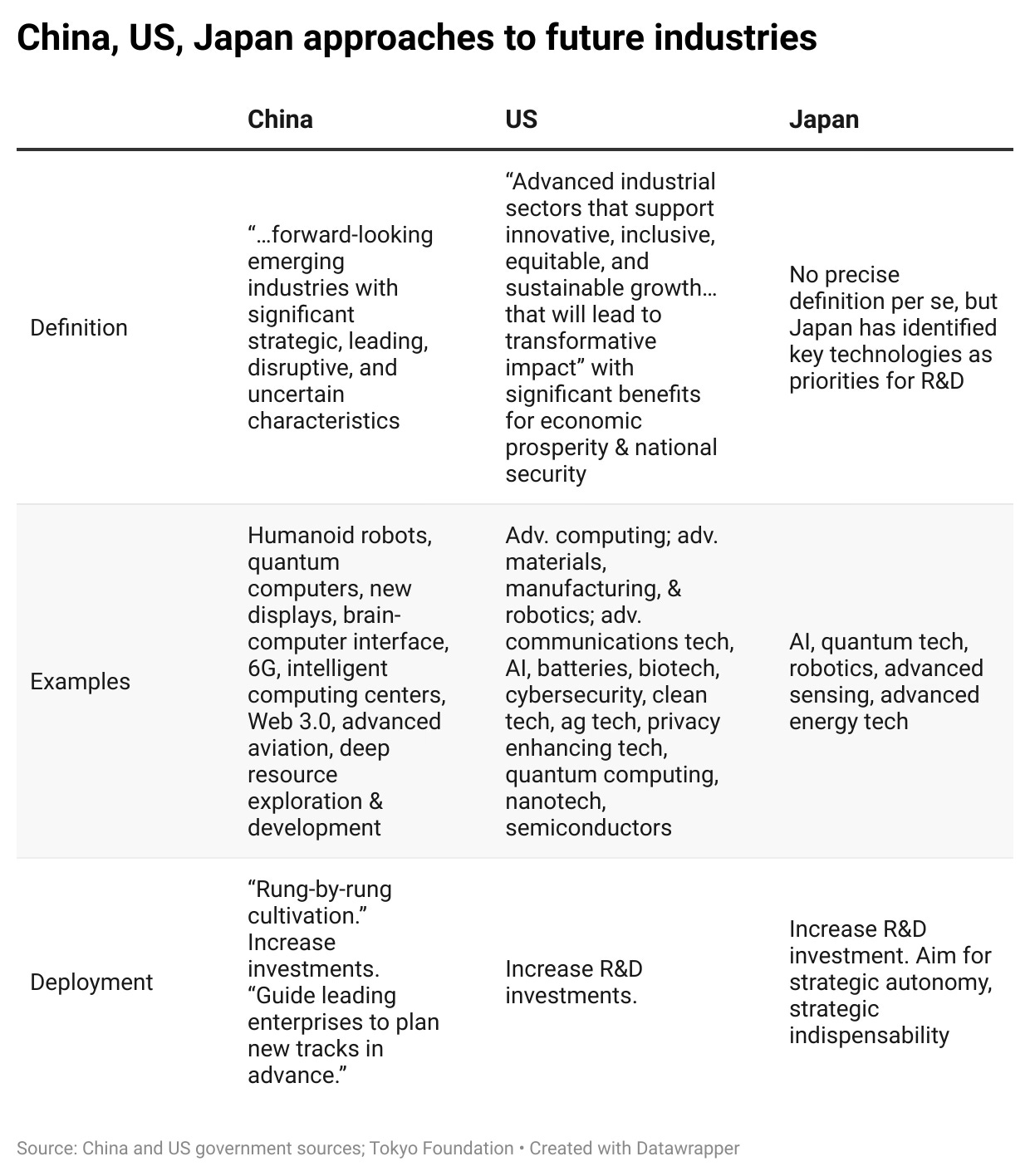

China isn’t alone in scoping out industries of the future, of course. The Trump administration in 2019 published a report titled “America Will Dominate the Industries of the Future,” which has since been widely cited by Chinese analysts and researchers. The EU has been talking vaguely about “Industry 5.0.” And Japan has an initiative called the Program for the Development of Key Technologies for Economic Security (K-Program for short), focusing on five technologies including AI and quantum that are key to security.

Obviously, developing future industries will require heavy R&D investment. Countries are clear on that.

Where China differs is its approach: it recognizes that “seizing the commanding heights” of cutting-edge technology requires mobilizing entire industrial ecosystems and building out complete industry chains, with companies dotted throughout to ensure capabilities in key materials and components.

Beijing’s call for “rung-by-rung cultivation” of future industries reflects this understanding. Arguably, it is this whole-of-industrial-chain approach that has fueled China’s dominance of EVs, batteries, ands solar. No surprise, then, that it hopes to leverage that playbook again.

There’s no guarantee that China will replicate its success with strategic emerging industries in future industries. For one, much of the basic research for technologies like batteries and solar had already been done by the likes of the US and Japan; China’s heavy lifting came in scaling and commercializing. By contrast, many future technologies, like quantum computing, will require far more primary innovation.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences boiled it down to this: for China to move from strategic emerging industries to developing future industries, it will need to “change from imitation innovation to independent innovation.”

Related reading from a/symmetric:

Weekly Links

🖇️ Clean energy innovation in China. “Countries and firms seeking to catch up or simply compete in the clean energy field may need to consider a broader approach than just reducing costs or scaling up on the backs of subsidies given both the advantages and disadvantages of production disaggregation,” writes researcher Anders Hove. (Oxford Institute for Energy Studies)

🖇️ Chinese battery makers’ trade barrier workarounds. “At present, Chinese battery companies are following two paths to expand overseas: one is to expand into the European and American markets by using energy storage batteries; the other is to try new cooperation models and achieve light-asset and low-risk overseas expansion by exporting technology.” (Economic Observer, in Chinese)

🖇️ Japan’s dependence on Chinese imports almost doubled in the three years to 2022, according to a white paper from the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. The paper, in Japanese, can be found here; a translated version is expected “at a later date.” (Yicai Global)