This week:

China’s innovation gauge: a new national system scores companies on innovation, and directs state funds towards high scoring ones. Simple idea, complex execution.

Weekly Links: China’s upstream muscles, the EV innovation flywheel, process and original innovation

Tallying China’s innovation

Can you industrial policy your way to innovation? China is wagering that it can. And a lot hangs on that bet.

This week, the Chinese government rolled out a national “innovation points system.” Described as a “financial policy tool” to boost technological progress, it rates businesses on how innovative they are, then directs money towards high scoring ones.

The thinking is that Beijing can marry the firepower of its state capital with tech firms doing high risk, high returns work—and in doing so accelerate the country’s pursuit of original innovation. The idea is simple, its execution will almost certainly be more complex, and whether the program succeeds remains to be seen.

Creating a national “innovation points system”

The innovation points system has been several years in the making. Research on it began in 2019 under the direction of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST). A pilot program launched in 2020 across 13 national high-tech zones, with the Hangzhou hub—which spawned giants like Alibaba, Hikvision, and Dahua Technology—taking the lead. In 2022, MOST published a pilot list of 500 companies scored for their innovativeness and recommended to state banks for special loans. Some are well known, others less so. All are in either start-up, growth, or late stages.

Now, after four years of experimentation and tweaking, MOST has launched the innovation points system nationwide. While the scoring system has so far been used to approve or fast track loans to innovative firms, the aim is to expand its use to eventually inform industrial policies, equity investments, and public listings.

One might wonder how exactly to measure firms’ propensity for innovation, and whether what’s measured is what matters. According to guidelines published this week, MOST’s approach takes into account factors including the following, with weightings adjusted as companies mature:

R&D expenditure: total, growth, share of revenue

Science and technology staff as share of total headcount

Number of patent applications related to the main business

Value of enterprise technology contract transactions

Revenue from high-tech products; revenue growth rate

Tax exemptions from R&D expenses

Number of science and technology prizes and projects awarded and undertaken at or above the provincial level

Amount of venture capital investments received

…but will it lead to more innovation?

Still, having criteria for a firm-level innovation index is one thing. Whether those criteria incentivize the right or best kind of innovation is another.

One can imagine a scenario in which businesses go through a box ticking exercise to score high innovation points and land lucrative loans, but don’t actually manage to make the frontier-pushing innovations that Beijing seeks.

Then there’s the risk that firms score high innovation points by fudging their performance in the various criteria. Researchers Alicia García-Herrero and Michal Krystyanczuk, for example, have found that innovative small- and medium-sized companies selected for China’s “little giants” industrial policy program don’t comply with the listed criteria any more than other comparable domestically listed companies.

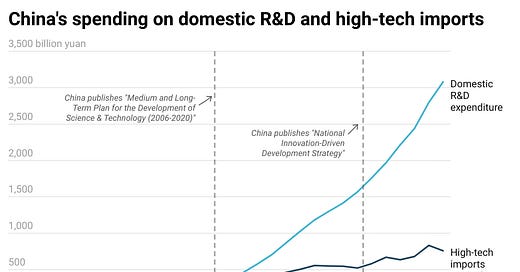

One thing is clear: as shown by the chart below (we have previously shared a similar one), China’s industrial policies can be powerful behavioral nudges for companies, universities, and researchers. But the grand prize lies in leveraging those actions to achieve actual strategic objectives, in this case superiority in critical and future technologies. And that’s easier said than done.

Weekly Links

🖇️ Industrial policy for innovation. Related to the discussion above, the Peking University economist Huang Yiping makes what is an implicit argument for Chinese industrial policy to shift from targeting process innovation to original innovation. He writes, in Chinese: “The central government and local governments should focus on overcoming technological bottlenecks in supporting industrial development, rather than simply supporting everyone to use existing technologies to replicate production capacity. Industrial policy is very important, but the key is to support technological innovation, rather than the simple replication of similar industries.” (Jiemian)

🖇️ Beijing will restrict exports of antimony, a mineral used in clean energy and military technologies. The curbs follow similar restrictions last year on graphite, germanium, and gallium. One observation: compared with US export restrictions that largely target downstream products, China has plenty of upstream muscles to flex. (Reuters, Force Distance Times)

🖇️ EV innovation flywheel. State media has a pithy piece on why Chinese carmakers are reshaping the global automotive landscape: “In addition to the first-mover advantage, the cost advantage of China's production, the vertical integration of the supply chain, the high degree of integration, and the continuous iteration of technology are all important reasons why China's new energy vehicles have an advantage.” (Economic Information Daily)

Good to see that China is coming face to face with their biggest weakness: innovation. Only time will tell if they will succeed, but the fact that they are placing proper incentives in place is promising.

I worked with Chinese SOEs in the power and industrial sector. This won't succeed. Guarantee it. Chinese SOEs, always take the cheap politically correct course. They never admit failure and rarely course correct. They are also incredibly lazy. At Chinese power plants I would point out small issues for them to correct and they would never do it. They don't maintain things, preferring to buy new in order to have a constant supply of replacements in order to have a revenue source for graft. But only for budgeted items. If something needed to be replaced that wasn't budget they would just find a way around it. Example at a power plant in Changchun one of the probe we supplied was run over and broken off by a fork lift. Well things happen so replace the probe, that's what would happen in the U.S. Not in China. They could have welded the probe also, not as good but cheaper. They didn't do either. What they did was use the probe which gave them an incorrect signal for the amount of air going into one duct for the pulverizer. This is critical measurment. And they manipulated it to make it LOOK correct. So that plant wasted lots of coal and created unnecessary amount of NOx due to inattention. At another plant I went to in Shanghai, the plant had problems with dust preventing measurement. No problem, we had a device for that but they didn't want to solve that problem. I also noticed they didn't have enough probes to get a good measurement. Here again, no interest to fix the problem. Finally I noticed the probes were in the wrong way. No problem, during a plant shutdown take the probes out and shift them 90 degrees on this square duct. Drill new holes, weld over the old holes, reconnect the signal lines. Easy. Would take 1/2 day at most per duct. Get a better measurement and save a lot of money, except this was a Chinese SOE who are basically allergic to work. They just left the probes in the wrong way. In theory China wants to do a lot of things, at the working level though implementation is always terrible. The only real way to get these problems sorted out is for the SOEs to be in a JV with a foreign company that takes over some of the management of their operation which will never happen in China. I have worked with SOEs in other countries like Taiwan. Also screwed up, but not THAT screwed up and way less lazy.